Note: This article is an update and merge of two articles originally published in 2014. It is dedicated to the memory of the victims of the bombing, and to Keith Woods who did so much to ensure that they were not forgotten.

In October 2013, the London Borough of Tower Hamlets invited residents to nominate a person, place or event in the borough they feel should be commemorated with a blue “People’s Plaque”. They included a list of 17 candidates for a blue plaque, including one titled The bombing of a public shelter on Bullivant’s Wharf, Isle of Dogs, with the description:

On the night of March 19, 1941, a public shelter on Bullivant’s Wharf, off Westferry Road, was hit by a landmine. Over 40 people were killed, and dozens were injured. Some families lost all but one member. This was the Isle of Dogs’ biggest wartime disaster….

I had heard of this terrible incident, but I did not know anything about it. A quick search on the internet did not reveal much more – and even Islanders were not too sure of the facts. It seemed to me to be a forgotten tragedy. Over 40 people killed in one bombing was significant even by the standards of the East End during WWII. Why was there no memorial to the victims? Why was it that nobody even seemed to be sure where the shelter was? Reasons enough to investigate further….

Shelter Arrangements

At the start of the war, there were no purpose-built shelters. Based on experience of aerial bombing during WWI, it was not expected that more protection would be required than that offered by basements, crypts, railway arches and similar. The government was also concerned that a large-scale building of underground shelters (as was happening in Berlin) would serve only to cause unnecessary panic.

During the so-called ‘phoney war’ of 1939, the government was even reluctant to allow use of tube stations as shelters, as they were genuinely worried that Londoners would move underground and not want to come back up to the surface.

Anderson shelters were an option for those with gardens to accommodate them. Although they look less than sturdy, Anderson shelters turned out to be extremely strong and effective when covered in earth as prescribed. They could not withstand a direct hit (nor could even a concrete shelter), but they were very effective at withstanding blasts and the force of buildings, walls or other heavy objects collapsing onto them. As this photo shows, although the house is destroyed, the Anderson shelter is intact. The inhabitants survived the raid.

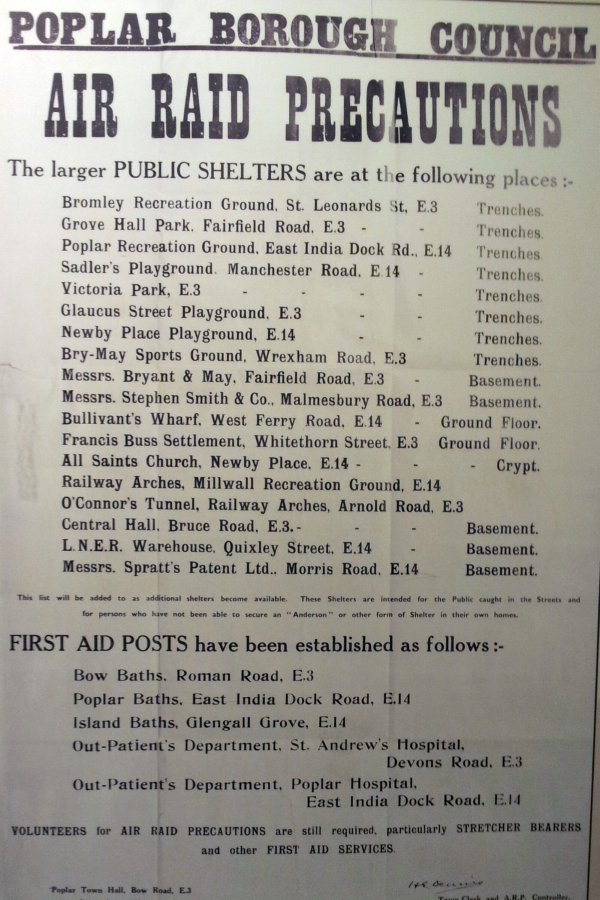

However, only 25% of Londoners had a garden, and it fell to local borough councils to make arrangements for communal shelters. In 1939, Poplar Borough Council issued posters showing the locations and types of official shelters:

This poster shows that the only purpose-built shelters were to be offered by trenches built in parks. The trenches were not dissimilar to those built during WWI, and were usually covered in corrugated iron roofs and earth. They were damp and mouldy, flooded when it rained, but – worse than that – the sides would too easily collapse on the inhabitants if there was an explosion close by. More than 100 were killed in Kennington Park, South London, in October 1940 when an entire trench system was destroyed by the shock waves of a 50 lb bomb that hit one section.

The Blitz revealed the dangers of trenches and similar shelter arrangements and spurred the Ministry of Home Security into the large-scale construction of purpose-built air raid shelters – frequently built with a combination of brick and concrete, and identified by the ubiquitous ‘S’ for shelter.

These were mostly small-scale shelters that accommodated not too many people. This was more due to necessity than design, but there remained doubts about the wisdom of large public shelters

Bullivant’s Wharf

In 1883, William Bullivant opened his wire-rope company at 38 Westferry Road (the present-day zebra crossing near Topmast Point crosses Westferry Road at this point).

The shelter named in the Poplar Borough Council poster was somewhere on this wharf, but where, precisely? I asked around, and answers from two old Islanders pointed to a location by the river. Arthur Ayres:

I remember the shelter being bombed. Although I was about 7 or 8 at the time these things leave a permanent mark in the memory. As I understood it at the time the shelter received a more or less direct hit and some of the wreckage fell into the river.

And, Peter Wright’s uncle, Frank Wright, who himself lost an uncle in the bombing of Bullivant’s Wharf:

It was the building next to the river and not the one near Westferry Road side.

According to British History Online:

A prominent warehouse adjoining London Wharf, apparently built in 1897, was extensively reconstructed as ‘Stronghold Works’ for British Ropes in 1934. Half of two tall storeys, half of four storeys, it was a substantial brick-built structure with reinforced-concrete floors. The fourth floor was used for engineering.

The appropriately named ‘Stronghold Works’ is the tallest of the riverside buildings in the following 1937 photo.

Most of the buildings in this photo belonged to Bullivant’s Wharf (the name, ‘Stronghold Wharf’ name is possibly a mistake – however, wharf names had no official standing anyway, they were simply given their names by the wharf owner, and thus changed frequently). Photo: Port of London Authority

It was almost certainly this building that housed the later public shelter, which had a capacity of 400 people seated and 200 in bunks.

“The Wednesday”

On Wednesday 19th March 1941, between 8 pm and 2 am, in a massive assault made by 479 Luftwaffe bombers, 470 tonnes of high explosive and more than 120,000 incendiary bombs were dropped on London. The targets, illuminated by parachute flares, were the dock installations along the Thames, from London Bridge to Beckton. Fire watchers assessed afterwards that there were close to 1900 separate fires.

A passage in “The Story of the Friends Ambulance Unit in the Second World War” (published by George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1947) makes a short reference to what happened at Bullivant’s Wharf:

The patrol had set out for it in the middle of a raid. A fresh burst of activity drove it back for a while to the shelter which it had just left. It was a few minutes later that the bomb fell on a corner of the wharf. The entire warehouse was covered by a single roof; when the bomb exploded the walls tottered for a moment, the roof fell in, and the whole shelter population was buried in the debris. It was estimated that there were about 180 people in the shelter at the time….

Writing on http://www.islandhistory.org.uk, Keith Woods, who had also been researching the incident (and who counted family members among the victims), quoted Joyce Jacobs’ recollections of the evening:

We had our blankets and our kettle and all the things you took up there and we were going out the front door when it was really banging overhead. The guns and the planes and the bombs. So he said, “Hang on a minute” because you could get hit with shrapnel, running through it. Good job we did. We’d have been up there as well. Soon after, someone came running down the street. “Bullivant’s been hit. All the people in the shelter…” And they were bringing out the dead. And a woman drove the ambulance backwards and forwards through that, taking all the injured up to Poplar Hospital.

According to Joyce, the high death toll was due to particular circumstances: “A 56 bus, which was pretty full, pulled in there and emptied out all the people. The raid was so bad, the driver wouldn’t go on, so he pulled in there so everybody could get in the shelter.”

Keith also quoted Margaret Corroyer, who lost many family members in the bombing:

My memory of that night was of regaining consciousness and being pinned down, unable to move whilst a choking stream of dust filled my mouth and nose. I recall the journey to Poplar Hospital and afterwards thought I must have imagined a person on the stretcher above, but have since been told it was so. A horrific experience to lay there and feel something sticky dripping from above.

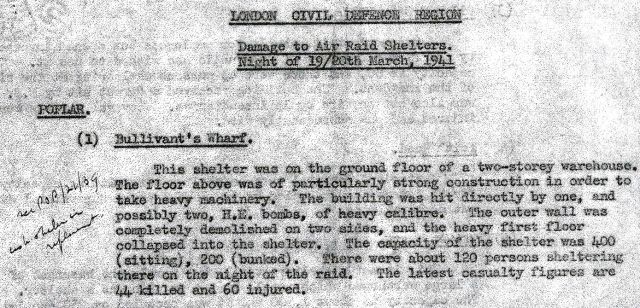

There were approximately 120 people in the shelter, and at least 40 had been killed, and a further 60 injured. This was to be the worst bombing incident on the Isle of Dogs during WWII.

This list of victims is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (Civilian Victims). It contains 41 names, and not 44 as mentioned in the Strutt’s WWII report, below. The precise number is unclear:

Sadly, similar incidents were being reported from other parts of London. It is estimated that 631 Londoners were killed in what was the largest bombing raid since December 1940, with West Ham, Stepney and Poplar suffering particularly badly. On 23rd March, Downing St asked for details of the events of that night.

Two days later, the London Civil Defence Region supplied “Strutt” with the information he was to provide to the Prime Minister:

This same report describes also the damage on 19th March to shelters in Cording Street, Bow Road, Quixley Street (all in Poplar), and Brunton House, Cowley Gardens, Oil and Cake Mills, Leith Road and Orient Wharf (all in Stepney).

The investigations formed the basis for repairs and improved shelter design; the incidents had confirmed the government’s concerns about large public stelters, especially those that were not purpose-built. In the case of Bullivant’s Wharf, the building was totally destroyed and there was no attempt to repair or replace it.

1941. Temporary repairs to river wall at Bullivant’s Wharf. The destroyed building was to the left of the sandbags (one thousand of which were required for the repair). Source: The Thames at War by Gustav Milne.

Very shortly afterwards, Poplar Borough Council cleared the land and their Works Department used it for storage. By the time of the following photo, taken in 1950, the wharf had been taken over by wharfingers, Freight Express Ltd.

1952. A section of the former Bullivant’s Wharf. The riverside crane is on the site of the destroyed shelter. Image: http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk

Freight Express later merged with Seacon and created a large shipping terminal on the site.

Seacon was one of the last industrial firms to close on the Island and was demolished in 2003. The new apartment block, Seacon Tower, was built on its site.

Memorial

Somewhere close to Seacon Tower would have been a perfect location for the People’s Plaque had the Bullivant’s Wharf tragedy been selected, but this was not to be.

Keith Woods, already mentioned above, decided that he would arrange a plaque himself in that case, so determined was he to make sure that there was a memorial to the victims. It was Keith’s persistence – with help from (then) Councillor Gloria Thienel pushing people at Tower Hamlets Borough Council – that ensured permission was granted for the placing of a plaque.

I am proud to say I also provided a very small contribution, writing the text for the plaque. And I enjoyed email discussions with Keith as we tried to establish precisely where the air raid shelter was located. Mind you, the emails were a bit confusing sometimes. Keith was not so computer-savvy by his own admission, and had to use his wife’s email account, causing me to explain to my own wife who this ‘Anne’ was who kept emailing me.

Keith’s determination extended even as far as paying for the plaque and personally fixing it in place on the wall on Thames Path. If you want to visit it yourself, it’s on the wall opposite Seacon Tower. Keith was also thankful to the concierge of that building (not sure if that’s his title), who was great. Seeing what Keith was up to, he provided assistance, tools and fixing materials.

The location was chosen because it was the closest piece of wall to the former air raid shelter that could be found. Mounting it on a fence or wall on the inland side of the Thames Path was problematic, as this was all private property, and even the council was not quite sure who owned the fence and wall along the riverside. But, in the end, Keith scouted the path and found a nice piece of wall which could not be closer the location of the WWII air raid shelter….just a couple of yards away.

At noon on Saturday 5th July 2014, a ceremony took place to mark the unveiling of the plaque. Actually, ‘ceremony’ is too sombre a word for what was a very informal and friendly event. Everyone was so pleased that the victims were finally getting a memorial, and there was plenty of reminiscing among the many old Islanders who were present (including plenty from the Island History Trust), some of whom had lost family or friends in the bombing, and some of whom only just missed being in the shelter themselves at the time.

Tower Hamlets councillor Andrew Wood was present, as was some weird looking bloke wearing a back to front hat (you know who you are 🙂 ).

Con Maloney was kind enough to distribute print-outs of the blog article I had written on Bullivant’s Wharf a few months ago

Keith’s cousin Donald gave a short speech at the end of events.

Afterwards, many of the group made their way to the George for fish & chips and drinks. Thanks also to the landlord and staff of the George for their hospitality.

The unveiling of the plaque was a great success, and I hope lots of people see it and want to find out more about what happened during the night of 19th and 20th March 1941. As much as I hope it keeps alive the memory of those who lost their lives that night.

Here are just a few of the many photos taken at the unveiling.

To think that I lived in Mellish St & went to St Luke’s & did not know. Just feel totally overwhelmed with sadness.

A very important piece of research, I have done a bit of research on the subject and like you came up with conflicting evidence. The piece from the Friends Ambulance service was especially confusing.

It was difficult to even place where Bullivant’s Wharf was !

It does seem strange that a place with such a large loss of life is not remembered , but we have to remember a large number of Islanders were dispersed during and after the war.

Excellent piece about an important part of the Island’s history.

I am (99%) certain that it was on the river front, where the new apartment tower block is, as indicated in the article. Always that 1% doubt, but I didn’t stop investigating this one……

https://www.museumoflondonprints.com/image/322024/avery-illustrations-thames-riverscape-showing-stronghold-wharf-and-bullivant-wharf-1937

Pingback: Unveiling of Bullivant’s Wharf Plaque | Isle of Dogs - Past Life, Past Lives

My great grandfather was killed on the same night apparently he stayed in his block of flats (Providence House) & went out on the balcony after the all clear but a stray device exploded & he was killed along with a couple of other people.

I saw the plague of the wall the other day whilst doing my daily jog past there, didnt know any of this and sad that it took so long to reconise this, well done to those involved

Richard Murrell was my great-great-grandfather and worked as a stevedore. My grandfather told me stories about him & the family who all lived on the island.

Wow. I have just started researching my family tree and lost two members of my family in this tragedy – Lilian and Margaret Corroyer. Thank you so much for sharing this information

I am impressed at the level of research you have done. I would be very pleased with that work in any of my own research pieces, and came to this blog because I saw the marble plaque at the site and it made me think.

Pingback: War Damage to Shelters in Poplar | Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives

Pingback: Everything you wanted to know about Alpha Grove but were afraid to ask | Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives

Pingback: A Walk Round the Isle of Dogs in 1968 (Then & Now) – Part I, Westferry Road | Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives

Pingback: Seacon | Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives

My grandfather, William Pettitt, born 1872, from West Ferry Road, was an Air Raid Warden killed while on duty during a raid, but there is no traceable record of his death anywhere that I can find of where or when he died. He may be one of the 3 missing names from the death tally, perhaps because his remains were unidentifiable. If anybody has any information confirming his likely presence, or anything about his life, I would very much like to hear of it.

Dear Malcolm Pettitt,

A Samuel Pettitt age 45 of 554 Manchester Road, Isle of Dogs died in Poplar Hospital on !/1/44.

Sadly, Mr Pettitt probably died has a result of a German air raid.

From Alfred Gardner.

Thank you for your reply. I am interested to record any information regarding the Pettitt family. It is frustrating that my Grandfather William Pettitt could die while on duty as a warden, without any official record, or even hearsay evidence of the event. However, I feel that the excellent article describing what is known of the Bullivents wharf disaster has been a revelation.

Dear Malcolm Pettitt,,

The date on my previous email should read 1/1/1944.

From Alfred Gardner.

Ada Barbara HAYNES was a 2nd cousin to my husband. She and her father Frank Rupert HAYNES were killed in this incident. I have discovered this through family history research.

Pingback: Little Remnants of Isle of Dogs History | Isle of Dogs – Past Life, Past Lives

My late mum’s mother sister and sister in law surname Shields all from Mellish Street were all killed in the tragedy. My mum was only 21 years old.

My daughter and me are coming up to London to pay our respects.

I was very interested in this article and want to add what I have been told over the years. My husband’s aunt, Ellen Baggs drove the wounded to Poplar hospital that night, she went backwards and forwards along roads that were seriously damaged but kept going until there were no more casualties to take. Lal Bennett told me not long before she died that she never understood why Ellen didn’t get any recognition as she was “a Saint” according to Lal. I know that she certainly was a woman to be reckoned with but she had a heart of gold, perhaps this will jog some memories!