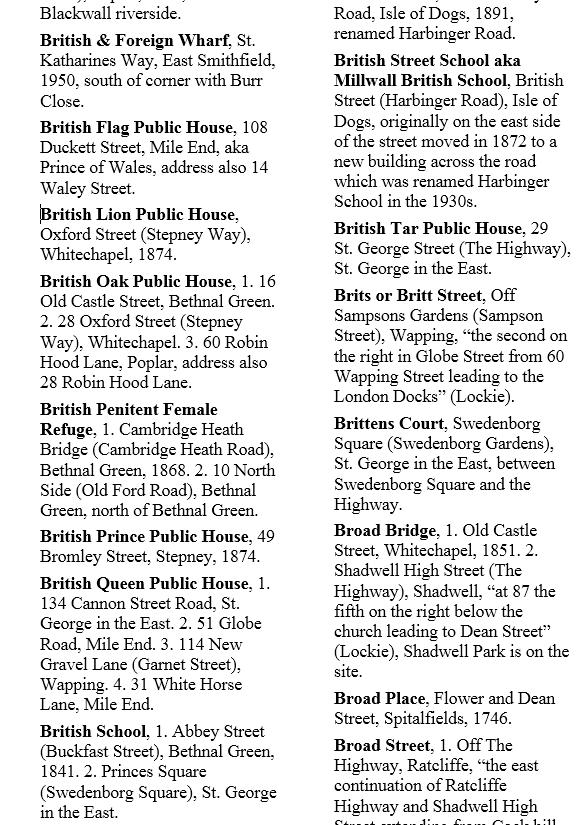

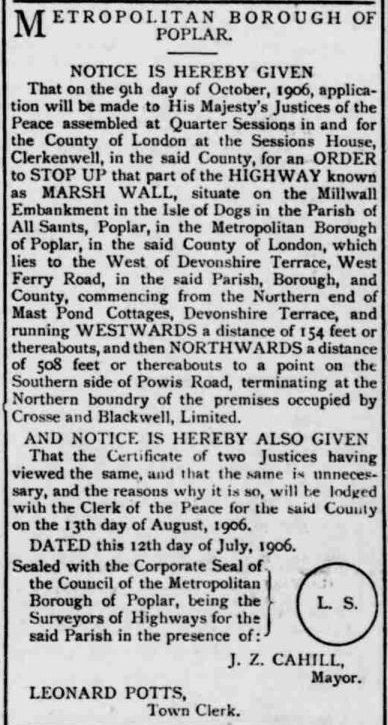

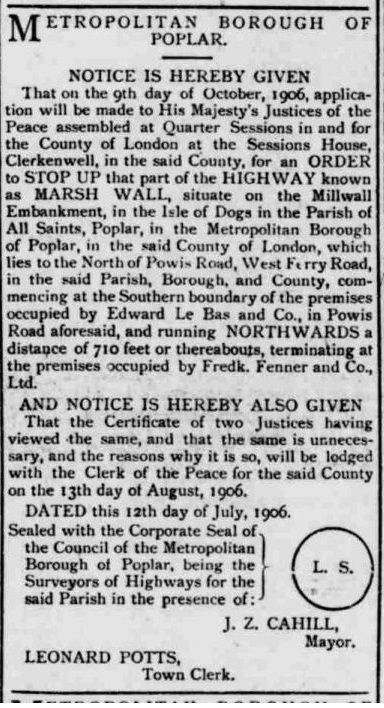

Ask most people to name the old road bridges on the Island, and they will probably mention Kingsbridge, the Blue Bridge (or its predecessor), the Glass Bridge (or its predecessor) and the swing-bridge in Preston’s Rd. There were however, two more: both between Limehouse and the City Arms, along the Walls. You’d be forgiven for not knowing about them, though, as they were removed a very long time ago.

North Limehouse Entrance Lock Bridge

If you were travelling around the Island from Limehouse in the late 1800s, the first bridge you would encounter was a swing-bridge which spanned the Limehouse Entrance Lock (the entrance to Limehouse Basin). Not to be confused with the Regent’s Canal Dock north of Narrow Street, which is often incorrectly-named Limehouse Basin, the actual Limehouse Basin was formerly at the west end of the West India Docks.

Originally constructed from timber, the first bridge was not reliable, and it was replaced by an iron bridge in 1810.

1890

Limehouse Lock was closed in 1894 on completion of the Blackwall Entrance Lock in Preston’s Rd. The lock and basin were filled in at the end of the 1920s, but the bridge was not dismantled and removed until 1949.

Almost complete filling of Limehouse Basin – looking west towards the Walls – bridge centre background.

1937

Site of the bridge in the 1980s.

Difficult to show a contemporary view as Westferry Circus is on the spot, but it is possible to mix up the maps.

South Limehouse Entrance Lock Bridge (aka City Arms Bridge)

Continuing south along the Walls, the next bridge spanned the South Limehouse Entrance Lock, providing ship access to the West India South Dock immediately north of the City Arms. Its vicinity to the pub led to it becoming known locally as the City Arms Bridge.

As with the bridge a little further north along the Walls (and built at the same time), this was originally a timber swing-bridge which was later replaced by an iron bridge; a bridge which was itself replaced in 1896.

In 1929, the PLA erected an impounding station – which is still functional – across the entrance lock, making the swing-bridge redundant. It was replaced by a fixed bridge in 1939.

Millwall Dock Entrance Lock Bridge (aka Kingsbridge)

Everybody I knew referred to it as Kingsbridge but that was never its formal name. Formally, it never even had a name. It was just the iron swing bridge over the Millwall Dock entrance lock. People like to have a name for everything, though, and it and the area around it became known as Kingsbridge, named after the Kingsbridge Arms public house

When it was opened, this was the largest dock entrance lock in London, being 80 ft wide and nearly 200 ft long. This photo shows the construction of the inner lock gates (the outer gates were far more substantial, designed to better deal with collisions by ships).

1867

The dock entrance was originally designed to be shorter, but during construction it became apparent that rapidly-increasing ship sizes required the building of a larger entrance. This meant building a lock that extended further east, which in turn led to a slight rerouting of Westferry Rd. I have added the original route of West Ferry Rd in this 1895 map; it was clearly a much gentler curve.

The map also shows a footbridge (“F.B.”) passing over the middle lock gates. This was to allow pedestrians to cross the dock entrance even if there was a ship in the lock. It was a double swing bridge which appears in a couple of old post cards.

c1910

1921

A bridger in 1926. This photo was taken looking south. On the left is a glimpse of the Sailor’s Home that used to be next to the dock road entrance.

1930s

1936

Ships continued to grow in size and by the 1930s the middle lock gates (and, thus, the foot bridge) were becoming obsolete. The PLA had plans to alter the lock, but these plans were deferred due to the outbreak of WWII. During the war, in September 1940, bombing destroyed the middle gates and much of the surrounding machnery and lock structure. Directly after the war, financial restrictions prevented any reconstruction and the lock remained unused. By 1955, the cost of reconstruction could no longer be justified and the dock was dammed at its inner gate (on the dockside).

The building of a dam at the inner gate meant that the road bridge (aka “Kingsbridge”) had to remain in place, never opening, and crossing a lock that would never be used. The structural solution would have been to completely fill in the locks, but this would have been much costlier , something unthinkable in the austere 1950s. Instead, the lock was allowed to silt up on the river side until the bridge wasn’t even crossing water.

1970s

This 1981 photo taken by Dave Chapman from the roof of McDougall’s shows the situation perfectly.

1981

It would be 1990 before the lock was properly filled-in and the bridge removed; work carried out by Mowlem for the LDDC. The following photo was taken by Kathy Duggan not long afterwards, with Michigan House on the right, and the Kingsbridge Arms in the distance.

1990s

Today there is a slipway on the river side of the bridge and a watersports club on the dock side (which is now under threat by people who want to build more towers). You don’t have to look too hard, though, to see where the outer and middle lock gates were mounted, and the remains of lock machinery.

South West India Dock East Entrance (aka Blue Bridge)

The ‘Blue Bridge’ (never its official name) opened on 1st June 1969, and is the fifth bridge since 1806 to cross the east entrance to West India South Dock. Its design is based on traditional Dutch drawbridges, and at the time of its opening it was the largest single-leaf bascule bridge in Britain. Its hydraulic machinery is based on that used by the former ‘Glass Bridge’ (the high-level footbridge over the Millwall Inner Dock). Although built for economy and efficiency – it can raise or lower in one minute – it is an attractive bridge that was immediately liked by Islanders.

The first bridge was made of timber. It spanned the 45 feet wide entrance of what was in 1806 the City Canal, a canal that crossed the Island and met the river in the west at the location of the later City Arms. In subsequent years, the canal would be enlarged to become the West India South Dock. The timber bridge survived until 1842, when it was replaced by an iron swing bridge.

Due to the increasing sizes of ships it was decided to widen the dock entrance from 45 ft to 55 ft. Construction took place from 1866 to 1870, along with the construction of bridge no. 3, another iron swing bridge.

Manchester Rd looking north. Glen Terrace is on the left and the Canal Dockyard graving docks are on the right. The 3rd bridge over the West India South Dock entrance lock is visible in the distance.

The Blue Bridge predecessor, was a so-called double-rolling bascule bridge, of a type invented by William Scherzer in Chicago. It was placed in 1929 and was known for being incredibly noisy, with a ‘groaning’ sound that could be heard many hundreds of yards away.

I remember this old bridge very well…we used to live in Rugless House, East Ferry Rd, and you could actually hear the bridge when it was raised up – John Tarff

Still from the early 1960s film ‘Portrait of Queenie’. Queenie Watts watches the bridge open from the river side.

.

The bridge was slow and unreliable, and was frequently breaking down. For the Port of London Authority (PLA), this was an incredibly important bridge as it crossed the south dock entrance, the only way for ships to get in and out of the West India and Millwall Docks – the iron swing bridges at Kingsbridge and in Preston’s Rd having ceased operations a few years before (the Preston’s Rd bridge did still open on occasion but the lock there was capable of handling barges only).

When the PLA was faced with its latest repair and maintenance bill of close to £200,000, they decided in 1967 that it would make more sense to build a new bridge. This would not only be more cost-effective, a new bridge would also be faster and more reliable, thus increasing the speed at which ships could clear the lock. This was also of benefit to Islanders as they would spend less time waiting for bridges to open and close (known as ‘bridgers’, one of the most effective excuses for being late for school or work).

The Blue Bridge

The bridge parts were manufactured in Glasgow (ironic, considering the number of steel and bridge construction firms of Scottish origin that were operating on the Island until a few years before) and the bridge was assembled in a yard next to the entrance lock.

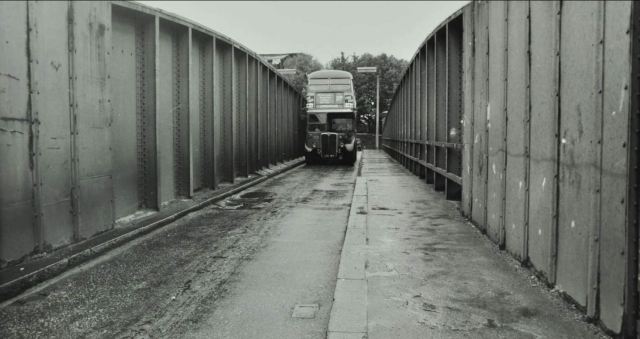

The old bridge had to be removed in order for the new bridge to be put in place. This meant that, for many months, no road traffic was possible over the only exit/entrance in the east of the Island. Bus passengers would disembark on one side of the lock, and then walk over the lock gates before catching another bus on the other side.

I remember…forever having to cross the lock to get a bus to Poplar scary at 12 years old – Becky Hobson

I am sure I lost property as we walked over those locks – Jill Leftwich

I was terrified of walking over that bridge. You could see the water through the wooden slats. Urgh! – Joan Reading

I remember when I was young we had to walk across the lock to the other side to pick up the bus to Poplar always thought I was going to fall in the water – Shelia Doe

Bridge Construction

My dad was lock foreman at the bridge, some times if I was there he would get me a lift on a tug through the docks and drop me off at the wooden bridge. I always wanted to work on the river, my dad said in the late 60’s don’t bother it’ll all be gone, how right he was. – Keith Charnley.

Bridger

I can remember getting bridgers when I went to secondary school at poplar – Lorraine Waterson

I remember at Sir Humphrey Gilbert school the kids coming in late to school “Sorry Sir gotta bridger” – Ted Whiteman

In 1976 I was fortunate enough to sail from the docks to the Netherlands (a trip organized by George Green’s Youth Club). The Blue Bridge had to be raised to allow our sailing boat to leave the dock. For the first time I was, in part, the cause of a bridger instead being held up by one. A rare experience. Also coincidental: a bridge based on Dutch design being raised to allow a ship to sail to the Netherlands, where I am as I write this, 40 years later.

Departing for the Netherlands (Photo: Mick Lemmerman)

Blackwall Entrance Lock (Preston’s Road) Bridge

British History Online:

In 1800 Ralph Walker designed a horizontal swing-bridge, double-turning and arched, the plans for which William Jessop used in 1801, in preference to his own designs, for a bridge over the Blackwall entrance lock.

The Blackwall entrance was very busy, and so Rennie had a cast-iron footbridge, supplied by Aydon & Elwell, erected over the east side of the lock in 1813, to allow the road bridge to stay open, unless carriage passage was needed, without inconveniencing pedestrians. Based on a bridge at Ramsgate designed by Rennie, it was 54ft long and only 4ft 6in. wide at the centre. The increasing numbers of workmen passing to and from the Isle of Dogs over this bridge necessitated a second footbridge in 1865, supplied by Westwood & Baillie. This improvement was negated in 1871 when one of the footbridges was moved to a City warehouse. The other was removed when the lock was rebuilt in 1893–4.

1890

1950. Preston’s Rd bridge on the right.

1962. Screenshot from ‘Portrait of Queenie’, with Queenie Watts

Like other bridges, the Preston’s Rd swing-bridge served no purpose eventually, Preston’s Rd was also straightened and widened to such an extent that it is difficult to recognise it as the same road.

Glengall (Road) Bridge, later Glass Bridge

The construction of the Millwall Docks in the early 1860s, made it impossible to get from one side of the other without travelling a long way south. The dock company reluctantly agreed to a public road across their land, and the first bridge was mounted over the Millwall Inner Dock in 1868.

1870, The bridge is in place, but the western end of Glengall Rd has not been constructed yet.

c1930

Glengall Bridge from the east.

British History Online:

The Glengall Road bridge became a nuisance both to local people and to the dock company. Its opening was a slow manoeuvre, and it often malfunctioned. Use of the Inner Dock by commercial shipping meant heavy wear and tear for a bridge that had not been designed for frequent opening. Repairs were made on nine separate occasions before 1930, causing much public inconvenience.

Reconstruction was approved in 1938:

Poplar Borough Council meeting minutes 1938

The start of World War II meant the reconstruction was not carried out. When the bridge broke down again in 1945, it was removed, and a wooden pedestrian bridge was buit on a moored barge. If a ship needed to pass, one end of the barge would be released and the barge pulled to one side.

Photo: Sandra Brentnall

Photo: George Charnley

After the war, the PLA stated its intention to close the public right of way across the Millwall Inner Dock, but this led to strong local opposition. The Council, the LCC and Charles Key, the local MP, forced the PLA to reconsider and prepare schemes for adapting the pedestrian crossing. In 1960 the PLA suggested either high-level footways with a double bascule bridge which would cost over £100,000, a tunnel under the dock for about £400,000, or a 180ft-high aerial cable car for about £50,000. The bridge option emerged as favourite, the tunnel being too expensive for the PLA and the cable car unpopular with the Council. A high-level bridge would keep the public out of the docks and allow barges to pass, opening only for ships.

1964

1964

1964

1965

The Glengall Grove high-level bridge gave the public the dubious privilege of a walk high over the Millwall Docks in an enclosed glazed tube. It was immediately renamed by Islanders, ‘The Glass Bridge’.

c1965

The ‘glass bridge’ immediately became a prime target for vandals and pedestrians were so intimidated that few used it. The PLA had to spend about £20,000 on repairs. Severe damage to the glass and the lifts in 1975–6 caused the bridge to be closed.

.

The bridge was closed and demolished by the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) in 1983.

Demolition

A temporary bridge was built across Millwall Inner Dock, allowing for road access across the dock for the first time since 1945.

The road access was short-lived, though: a new street – Pepper Street – was constructed through the former dockland, and this is closed to traffic. The eastern and western sections of Pepper Street are connected by the latest incarnation of Glengall Bridge.